7. Security¶

7.1. Introduction¶

Security vulnerabilities and attack vectors are everywhere. The Telecom industry and its cloud infrastructures are even more vulnerable to potential attacks due to the ubiquitous nature of the infrastructures and services combined with the vital role Telecommunications play in the modern world. The attack vectors are many and varied, ranging from the potential for exposure of sensitive data, both personal and corporate, to weaponized disruption to the global telecommunications networks. The threats can take the form of a physical attack on the locations the infrastructure hardware is housed, to network attacks such as denial of service and targeted corruption of the network service applications themselves. Whatever the source, any Cloud Infrastructure built needs to be able to withstand attacks in whatever form they take.

This chapter examines multiple aspects of security as it relates to Cloud Infrastructure and security aspects for workloads. After discussing security attack vectors, this chapter delves into security requirements. Regarding security requirements and best practices, specifications and documents are published by standards organisations. A selection of standards of interest for Cloud Infrastructure security is listed in a dedicated section. The chapter culminates with a consolidated set of “must” requirements and desired (should) recommendations; it is suggested that operators carefully evaluate the recommendations for possible implementation.

7.2. Potential attack vectors¶

Previously attacks designed to place and migrate workload outside the legal boundaries were not possible using traditional infrastructure, due to the closed nature of these systems. However, using Cloud Infrastructure, violation of regulatory policies and laws becomes possible by actors diverting or moving an application from an authenticated and legal location to another potentially illegal location. The consequences of violating regulatory policies may take the form of a complete banning of service and/or an exertion of a financial penalty by a governmental agency or through SLA enforcement. Such vectors of attack may well be the original intention of the attacker in an effort to harm the service provider. One possible attack scenario can be when an attacker exploits the insecure NF API to dump the records of personal data from the database in an attempt to violate user privacy. Cloud Infrastructure operators should ensure that the applications APIs are secure, accessible over a secure network (TLS) under very strict set of security best practices, and RBAC policies to limit exposure of this vulnerability.

Typical cloud associated attacker tactics have been identified in the widely accepted MITRE ATT&CK® Framework. This framework provides a systematic approach to capture adversarial tactics targeting cloud environments. Examples of such adversarial tactics are listed in the table below.

Attacker tactics |

Examples |

|---|---|

Initial Access |

Compromising user administration accounts that are not protected by multi-factor authentication |

Evasion |

Modifying cloud compute instances in the production environment by modifying virtual instances for attack staging |

Discovery |

Discovering what cloud services are operating and then disabling them in a later stage |

Data Exfiltration |

Moving data from the compromised tenant’s production databases to the hacker’s cloud service account or transferring the data out of the Communication Service Provider (CSP) to the attacker’s private network |

Service Impact |

Creating denial-of-service availability issues by modifying Web Application Firewall (WAF) rules and compromising APIs and web-based GUIs |

Table 7-1: Cloud attacker tactics - Examples

7.3. Security Scope¶

7.3.1. In-scope and Out-of-Scope definition¶

The scope of the security controls requirements maps to the scope of the Reference Model architecture.

Cloud Infrastructure requirements must cover the virtual infrastructure layer and the hardware infrastructure layer, including virtual resources, hardware resources, virtual infrastructure manager and hardware infrastructure manager, as described in Chapter 3.

7.3.2. High level security Requirements¶

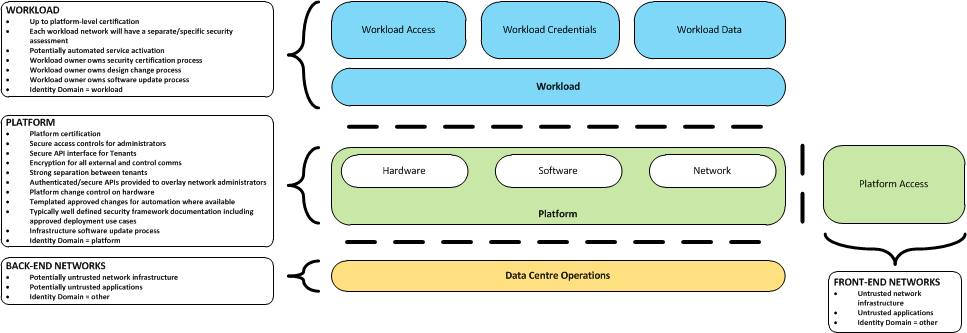

The following diagram shows the different security domains that impact the Reference Model:

Figure 7.1 Reference Model Security Domains¶

Note: “Platform” refers to the Cloud Infrastructure with all its hardware and software components.

7.3.2.1. Platform security requirements¶

At a high level, the following areas/requirements cover platform security for a particular deployment:

Platform certification

Secure access controls for administrators

Secure API interface for tenants

Encryption for all external and control communications

Strong separation between tenants - ensuring network, data, memory and runtime process (CPU running core) isolation between tenants

Authenticated/secure APIs provided to overlay network administrators

Platform change control on hardware

Templated approved changes for automation where available

Typically well-defined security framework documentation including approved deployment use cases

Infrastructure software update process

7.3.2.2. Workload security requirements¶

At a high level, the following areas/requirements cover workload security for a particular deployment:

Up to platform-level certification

Each workload network will need to undertake it own security self-assessment and accreditation, and not inherit a security accreditation from the platform

Potentially automated service activation

Workload owner owns workload security certification process

Workload owner owns workload design change process

Workload owner owns workload software update process

7.3.3. Common Security Standards¶

The Cloud Infrastructure Reference Model and the supporting architectures are not only required to optimally support networking functions, but they must be designed with common security principles and standards from inception. These best practices must be applied at all layers of the infrastructure stack and across all points of interconnections (internal or with outside networks), APIs and contact points with the NFV network functions overlaying or interacting with that infrastructure.

A good place to start to understand the security requirements is to use the widely accepted definitions and core principles developed by the OWASP, Open Web Application Security Project:

Confidentiality – Only allow access to data for which the user is permitted.

Integrity – Ensure data is not tampered with or altered by unauthorised users.

Availability – ensure systems and data are available to authorised users when they need it.

These 3 principles are complemented for Cloud Infrastructure security by:

Authenticity – The ability to confirm the users are in fact valid users with the correct rights to access the systems or data.

Standards organisations with recommendations and best practices, and certifications that need to be taken into consideration include the following examples. However this is by no means an exhaustive list, just some of the more important standards in current use.

Center for Internet Security - https://www.cisecurity.org/

Cloud Security Alliance - https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/

Open Web Application Security Project - https://www.owasp.org

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) with the special publications:

NIST SP 800-123 Guide to General Server Security

NIST SP 800-204A Building Secure Microservices-based Applications Using Service-Mesh Architecture

NIST SP 800-204B Attribute-based Access Control for Microservices-based Applications Using a Service Mesh

NIST SP 800-207 Zero Trust Architecture

FedRAMP Certification https://www.fedramp.gov/

ETSI Cyber Security Technical Committee (TC CYBER) - https://www.etsi.org/committee/cyber

ETSI Industry Specification Group Network Functions Virtualisation (ISG NFV) and its Security Working Group NFV-SEC

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) and IEC (the International Electrotechnical Commission) - www.iso.org. The following ISO standards are of particular interest for NFVI

ISO/IEC 27002:2013 - ISO/IEC 27001 are the international Standard for best-practice information security management systems (ISMSs)

ISO/IEC 27032 - ISO/IEC 27032 is the international Standard focusing explicitly on cybersecurity

ISO/IEC 27035 - ISO/IEC 27035 is the international Standard for incident management

ISO/IEC 27031 - ISO/IEC 27031 is the international Standard for ICT readiness for business continuity

In mobile network field, the GSM Association (GSMA) and its Fraud and Security working group of experts have developed a set of documents specifying how to secure the global mobile ecosystem.

The document “Baseline Security controls”, FS.31 v2.0[20], published in February 2020, is a practical guide intended for operators and stakeholders to check mobile network’s internal security. It lists a set of security controls from business controls (including security roles, organizational policies, business continuity management…) to technological controls (for user equipment, networks, operations…) covering all areas of mobile network, including Cloud Infrastructure. A checklist of questions allows to improve the security of a deployed network.

The GSMA security activities are currently focussed around 5G services and the new challenges posed by network functions virtualisation and open source software. The 2 following documents are in the scope of Cloud Infrastructure security:

The white paper “Open Networking & the Security of Open Source Software deployment”, published in January 2021 [21], deals with open source software security, it highlights the importance of layered security defences and lists recommendations and security concepts able to secure deployments.

The “5G Security Guide”, FS.40 version 2.0, Oct. 2021 [36](non-binding Permanent Reference Document), covers 5G security, in a holistic way, from user equipment to networks. The document describes the new security features in 5G. It includes a dedicated section on the impact of Cloud on 5G security with recommendations on virtualisation, cloud native applications and containerisation security.

7.4. Cloud Infrastructure Security¶

7.4.1. General Platform Security¶

The security certification of the platform will typically need to be the same, or higher, than the workload requirements.

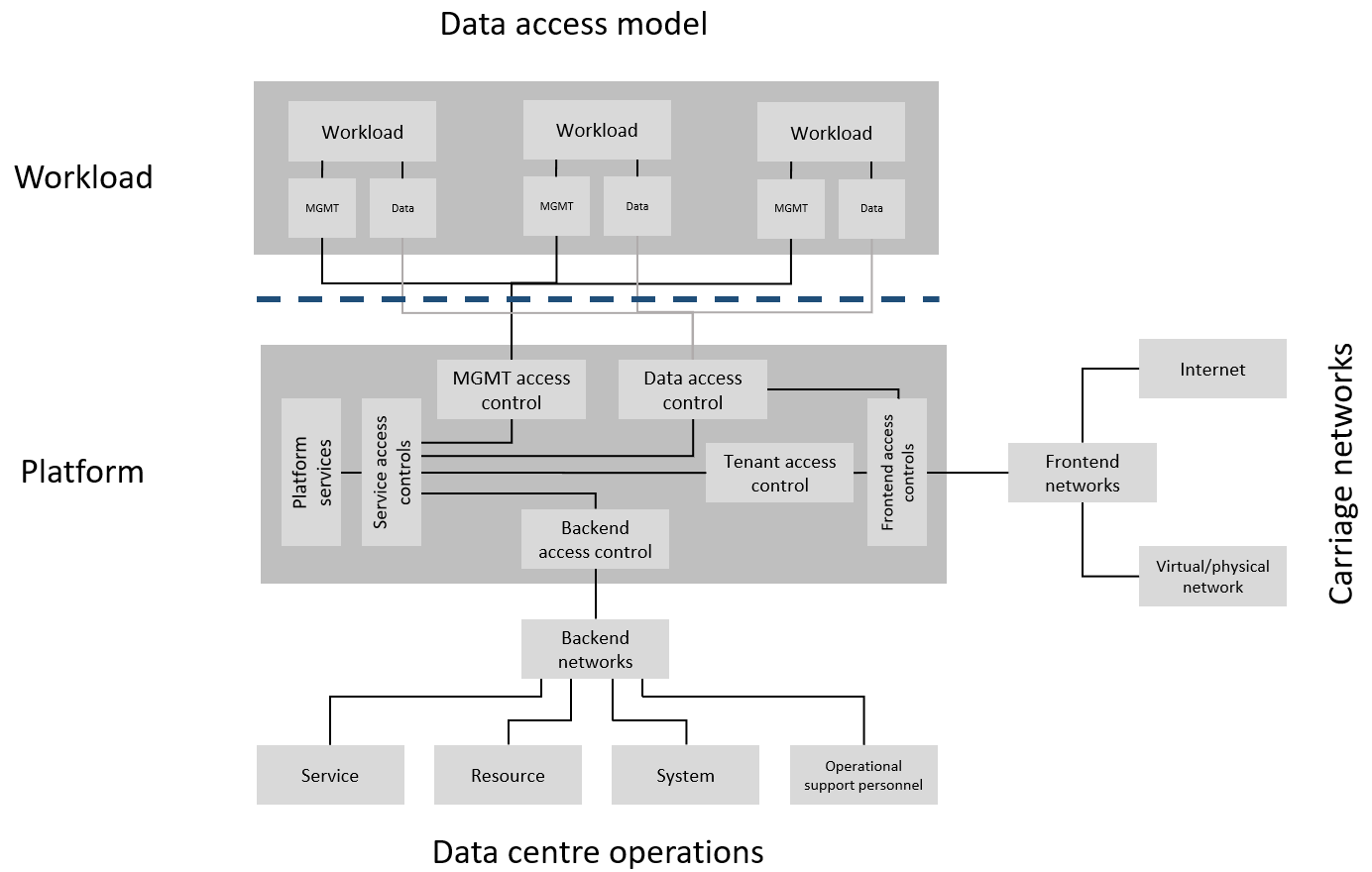

The platform supports the workload, and in effect controls access to the workload from and to external endpoints such as carriage networks used by workloads, or by Data Centre Operations staff supporting the workload, or by tenants accessing workloads. From an access security perspective, the following diagram shows where different access controls will operate within the platform to provide access controls throughout the platform:

Figure 7.2 Reference Model Access Controls¶

7.4.1.1. High-level functions of access controls¶

MGMT ACCESS CONTROLS - Platform access to workloads for service management. Typically all management and control-plane traffic is encrypted.

DATA ACCESS CONTROLS - Control of east-west traffic between workloads, and control of north-south traffic between the NF and other platform services such as front-end carriage networks and platform services. Inherently strong separation between tenants is mandatory.

SERVICES ACCESS CONTROLS - Protects platform services from any platform access

BACK-END ACCESS CONTROLS - Data Centre Operations access to the platform, and subsequently, workloads. Typically stronger authentication requirements such as (Two-Factor Authentication) 2FA, and using technologies such as Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) and encryption. Application Programming Interface (API) gateways may be required for automated/script-driven processes.

FRONT-END ACCESS CONTROLS - Protects the platform from malicious carriage network access, and provides connectivity for specific workloads to specific carriage networks. Carriage networks being those that are provided as public networks and operated by carriers, and in this case with interfaces that are usually sub, or virtual networks.

TENANT ACCESS CONTROLS - Provides appropriate tenant access controls to specific platform services, and tenant workloads - including Role-Based Access Control (RBAC), authentication controls as appropriate for the access arrangement, and Application Programming Interface (API) gateways for automated/script-driven processes.

7.4.1.2. Cloud Infrastructure general security requirements¶

System Hardening

Adhering to the principle of least privilege, no login to root on any platform systems (platform systems are those that are associated with the platform and include systems that directly or indirectly affect the viability of the platform) when root privileges are not required.

Ensure that all the platform’s components (including hypervisors, VMs, etc.) are kept up to date with the latest patch.

In order to tightly control access to resources and protect them from malicious access and introspection, Linux Security Modules such as SELinux should be used to enforce access rules.

Vulnerability Management

Security defects must be reported.

The Cloud Infrastructure components must be continuously analysed from deployment to runtime. The Cloud Infrastructure must offer tools to check the code libraries and all other code against the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) databases to identify the presence of any known vulnerabilities. The CVE is a list of publicly disclosed vulnerabilities and exposures that is maintained by MITRE. Each vulnerability is characterised by an identifier, a description, a date, and comments.

When a vulnerability is discovered on a component (from Operating Systems to virtualisation layer components), the remediation action will depend on its severity. The Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) allows to calculate a vulnerability score. It is an open framework widely used in vulnerability management tools. CVSS is owned and managed by FIRST (Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams). The CVSS consists of three metric groups: Base, Temporal, and Environmental. The Base metrics produce a score ranging from 0 to 10, this score can then be refined using Temporal and Environmental metrics. The numerical score can be translated into a severity qualitative representation: low, medium, high, or critical. The severity score (or the associated qualitative representation) allows organisations to prioritise the remediation activities, high scores mandating a fast response time. The vulnerable components must then be patched, replaced, or their access must be restricted.

Security patches must be obtained from an authorised source in order to ensure their integrity. Patches must be tested and validated in a pre-production environment before being deployed into production.

Platform access

Restrict traffic to only traffic that is necessary, and deny all other traffic, including traffic from and to ‘Back-end’.

Provide protections between the Internet and any workloads including web and volumetrics attack preventions.

All host to host communications within the cloud provider network are to be cryptographically protected in transit.

Use cryptographically-protected protocols for administrative access to the platform.

Data Centre Operations staff and systems must use management protocols that limit security risk such as SNMPv3, SSH v2, ICMP, NTP, syslog, and TLS v1.2 or higher.

Processes for managing platform access control filters must be documented, followed, and monitored.

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) must apply for all platform systems access.

All APIs access must use TLS protocol, including back-end APIs.

Workload security

Restrict traffic to (and from) the workload to only traffic that is necessary, and deny all other traffic.

Support zoning within a tenant workload - using application-level filtering.

Not expose tenant internal IP address details to another tenant.

All production workloads must be separated from all non-production workloads including separation between non-hosted non-production external networks.

Confidentiality and Integrity

All data persisted to primary, replica, or backup storage is to be encrypted.

Monitoring and security audit

All platform security logs are to be time synchronised.

Logs are to be regularly scanned for events of interest.

The cloud services must be regularly vulnerability and penetration tested.

Platform provisioning and LCM

A platform change management process that is documented, well communicated to staff and tenants, and rigorously followed.

A process to check change management adherence that is implemented, and rigorously followed.

An approved system or process for last resort access must exist for the platform.

Where there are multiple hosting facilities used in the provisioning of a service, network communications between the facilities for the purpose of backup, management, and workload communications are cryptographically protected in transit between data centre facilities.

Continuous Cloud security compliance is mandatory.

An incident response plan must exist for the platform.

7.4.2. Platform ‘back-end’ access security¶

Validate and verify the integrity of resources management requests coming from a higher orchestration layer to the Cloud Infrastructure manager.

7.4.3. Platform ‘front-end’ access security¶

Front-end network security at the application level will be the responsibility of the workload, however the platform must ensure the isolation and integrity of tenant connectivity to front-end networks.

The front-end network may provide (Distributed Denial Of Service) DDoS support.

7.4.4. Infrastructure as a Code security¶

Infrastructure as a Code (IaaC) (or equivalently called Infrastructure as Code IaC) refers to the software used for the declarative management of cloud infrastructure resources. In order to dynamically address user requirements, release features incrementally, and deliver at a faster pace, DevSecOps teams utilise best practices including continuous integration and continuous delivery and integrate information security controls and scanning tools into these processes, with the aim of providing timely and meaningful feedback including identifying vulnerabilities and security policy violations. With this automated security testing and analysis capabilities it will be of critical value to detecting vulnerabilities early and maintaining a consistent security policy.

Because of the extremely high complexity of modern telco cloud infrastructures, even minor IaaC code changes may lead to disproportionate and sometime disastrous downstream security and privacy impacts. Therefore, integration of security testing into the IaaC software development pipeline requires security activities to be automated using security tools and integrated with the native DevOps and DevSecOps tools and procedures.

The DevSecOps Automation best practice advocates implementing a framework for security automation and programmatic execution and monitoring of security controls to identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover from cyber threats. The framework used for the IaaC security is based on, the joint publication of Cloud Security Alliance (CSA) and SAFECode, “The Six Pillars of DevSecOps: Automation (2020)” [22]. The document utilises the base definitions and constructs from ISO 27000 [23], and CSA’s Information Security Management through Reflexive Security [24].

The framework identifies the following five distinct stages:

Secure design and architecture

Secure coding (Developer IDE and Code Repository)

Continuous build, integration and test

Continuous delivery and deployment

Continuous monitoring and runtime defence

Triggers and checkpoints define transitions within stages. When designing DevSecOps security processes, one needs to keep in mind, that when a trigger condition is met, one or more security activities are activated. The outcomes of those security activities need to determine whether the requirements of the process checkpoint are satisfied. If the outcome of the security activities meets the requirements, the next set of security activities are performed as the process transitions to the next checkpoint, or, alternatively, to the next stage if the checkpoint is the last one in the current stage. If, on the other hand, the outcome of the security activities does not meet the requirements, then the process should not be allowed to advance to the next checkpoint. In the section “Consolidated Security Requirements”, the IaaC security activities are presented as security requirements mapped to particular stages and trigger points.

7.4.5. Security of Production and Non-production Environments¶

Telecommunications operators often focus their security efforts on the production environments actively used by their customers and/or their employees. This is of course critical because a breach of such systems can seriously damage the company and its customers. In addition, production systems often contain the most valuable data, making them attractive targets for intruders. However, an insecure non-production (development, testing) environment can also create real problems because they may leave a company open to corporate espionage, sabotage by competitors, and theft of sensitive data.

Security is about mitigating risk. If operators do not have the same level of security regime in their non-production environments compared to production, then an additional level of risk may be introduced. Especially if such non-production environments accept outside connections (for example for suppliers or partners, which is quite normal in complex telco ecosystems), there is a real need to monitor security of these non-production environments. The gold standard then is to implement the same security policies in production and non-production infrastructure, which would reduce risk and typically simplify operations by using the same control tools and processes. However, for many practical reasons some of the security monitoring rules may differ. As an example, if a company maintains a separate, isolated environment for infrastructure software development experimentation, the configuration monitoring rules may be relaxed in comparison with the production environment, where such experimentation is not allowed. Therefore, in this document, when dealing with such dilemma, the focus has been placed on those non-production security requirements that must be on the same level as in the production environment (typically of must type), leaving relaxed requirements (typically of should or may) in cases there is no such necessity.

In the context of the contemporary telecommunication technology, the cloud infrastructure typically is considered Infrastructure as a Code (IaaC). This fact implies that many aspects of code related security automatically apply to IaaC. Security aspects of IaaC in the telco context is discussed in the previous section “Infrastructure as a Code security”, which introduces the relevant framework for security automation and programmatic execution and monitoring of security controls. Organisations need to identify which of the stages or activities within these stages should be performed within the non-production versus production environments. This mapping will then dictate which security activities defined for particular stages and triggers (e.g, vulnerability tests, patch testing, penetration tests) are mandatory, and which can be left as discretionary.

7.5. Workload Security - Vendor Responsibility¶

7.5.1. Software Hardening¶

No hard-coded credentials or clear text passwords in code and images. Software must support configurable, or industry standard, password complexity rules.

Software should be independent of the infrastructure platform (no OS point release dependencies to patch).

Software must be code signed and all individual sub-components are assessed and verified for EULA (End-user License Agreement) violations.

Software should have a process for discovery, classification, communication, and timely resolution of security vulnerabilities (i.e.; bug bounty, penetration testing/scan findings, etc.).

Software should support recognised encryption standards and encryption should be decoupled from software.

Software should have support for configurable banners to display authorised use criteria/policy.

7.5.2. Port Protection¶

Unused software and unused network ports should be disabled by default.

7.5.3. Software Code Quality and Security¶

Vendors should use industry recognized software testing suites

Static and dynamic scanning.

Automated static code review with remediation of Medium/High/Critical security issues. The tool used for static code analysis and analysis of code being released must be shared.

Dynamic security tests with remediation of Medium/High/Critical security issues. The tool used for Dynamic security analysis of code being released must be shared.

Penetration tests (pen tests) with remediation of Medium/High/Critical security issues.

Methodology for ensuring security is included in the Agile/DevOps delivery lifecycle for ongoing feature enhancement/maintenance.

7.5.4. Alerting and monitoring¶

Security event logging: all security events must be logged, including informational.

Privilege escalation must be detected.

7.5.5. Logging¶

Logging output should support customizable Log retention and Log rotation.

7.6. Workload Security - Cloud Infrastructure Operator Responsibility¶

The Operator’s responsibility is to not only make sure that security is included in all the vendor supplied infrastructure and NFV components, but it is also responsible for the maintenance of the security functions from an operational and management perspective. This includes but is not limited to securing the following elements:

Maintaining standard security operational management methods and processes.

Monitoring and reporting functions.

Processes to address regulatory compliance failure.

Support for appropriate incident response and reporting.

Methods to support appropriate remote attestation certification of the validity of the security components, architectures, and methodologies used.

7.6.1. Remote Attestation/openCIT¶

Cloud Infrastructure operators must ensure that remote attestation methods are used to remotely verify the trust status of a given Cloud Infrastructure platform. The basic concept is based on boot integrity measurements leveraging the Trusted Platform Module (TPM) built into the underlying hardware. Remote attestation can be provided as a service, and may be used by either the platform owner or a consumer/customer to verify that the platform has booted in a trusted manner. Practical implementations of the remote attestation service include the Open Cloud Integrity Tool (Open CIT). Open CIT provides ‘Trust’ visibility of the Cloud Infrastructure and enables compliance in Cloud Datacenters by establishing the root of trust and builds the chain of trust across hardware, operating system, hypervisor, VM, and container. It includes asset tagging for location and boundary control. The platform trust and asset tag attestation information is used by Orchestrators and/or Policy Compliance management to ensure workloads are launched on trusted and location/boundary compliant platforms. They provide the needed visibility and auditability of infrastructure in both public and private cloud environments.

7.6.2. Workload Image¶

Only workload images from trusted sources must be used. Secrets must be stored outside of the images.

It is easy to tamper with workload images. It requires only a few seconds to insert some malware into a workload image file while it is being uploaded to an image database or being transferred from an image database to a compute node. To guard against this possibility, workload images must be cryptographically signed and verified during launch time. This can be achieved by setting up a signing authority and modifying the hypervisor configuration to verify an image’s signature before they are launched.

To implement image security, the workload operator must test the image and supplementary components verifying that everything conforms to security policies and best practices. Use of Image scanners such as OpenSCAP or Trivy to determine security vulnerabilities is strongly recommended.

CIS Hardened Images should be used whenever possible. CIS provides, for example, virtual machine hardened images based upon CIS benchmarks for various operating systems. Another best practice is to use minimalist base images whenever possible.

Images are stored in registries. The images registry must contain only vetted images. The registry must remain a source of trust for images over time; images therefore must be continuously scanned to identify vulnerabilities and out-of-date versions as described previously. Access to the registry is an important security risk. It must be granted by a dedicated authorisation and through secure networks enforcing authentication, integrity and confidentiality.

7.6.3. Networking Security Zoning¶

Network segmentation is important to ensure that applications can only communicate with the applications they are supposed to. To prevent a workload from impacting other workloads or hosts, it is a good practice to separate workload traffic and management traffic. This will prevent attacks by VMs or containers breaking into the management infrastructure. It is also best to separate the VLAN traffic into appropriate groups and disable all other VLANs that are not in use. Likewise, workloads of similar functionalities can be grouped into specific zones and their traffic isolated. Each zone can be protected using access control policies and a dedicated firewall based on the needed security level.

Recommended practice to set network security policies following the principle of least privileged, only allowing approved protocol flows. For example, set ‘default deny’ inbound and add approved policies required for the functionality of the application running on the NFV Infrastructure.

7.6.4. Volume Encryption¶

Virtual volume disks associated with workloads may contain sensitive data. Therefore, they need to be protected. Best practice is to secure the workload volumes by encrypting them and storing the cryptographic keys at safe locations. Encryption functions rely on a Cloud Infrastructure internal key management service. Be aware that the decision to encrypt the volumes might cause reduced performance, so the decision to encrypt needs to be dependent on the requirements of the given infrastructure. The TPM (Trusted Platform Module) module can also be used to securely store these keys. In addition, the hypervisor should be configured to securely erase the virtual volume disks in the event of application crashes or is intentionally destroyed to prevent it from unauthorized access.

For sensitive data encryption, when data sovereignty is required, an external Hardware Security Module (HSM) should be integrated in order to protect the cryptographic keys. A HSM is a physical device which manages and stores secrets. Usage of a HSM strengthens the secrets security. For 5G services, GSMA FASG strongly recommends the implementation of a HSM to secure the storage of UICC (Universal Integrated Circuit Card) credentials.

7.6.5. Root of Trust for Measurements¶

The sections that follow define mechanisms to ensure the integrity of the infrastructure pre-boot and post-boot (running). The following defines a set of terms used in those sections.

The hardware root of trust helps with the pre-boot and post-boot security issues.

Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) adheres to standards defined by an industry consortium. Vendors (hardware, software) and solution providers collaborate to define common interfaces, protocols and structures for computing platforms.

Platform Configuration Register (PCR) is a memory location in the TPM used to store TPM Measurements (hash values generated by the SHA-1 standard hashing algorithm). PCRs are cleared only on TPM reset. UEFI defines 24 PCRs of which the first 16, PCR 0 - PCR 15, are used to store measures created during the UEFI boot process.

Root of Trust for Measurement (RTM) is a computing engine capable of making integrity measurements.

Core Root of Trust for Measurements (CRTM) is a set of instructions executed when performing RTM.

Platform Attestation provides proof of validity of the platform’s integrity measurements. Please see Section “Remote Attestation/openCIT”.

Values stored in a PCR cannot be reset (or forged) as they can only be extended. Whenever a measurement is sent to a TPM, the hash of the concatenation of the current value of the PCR and the new measurement is stored in the PCR. The PCR values are used to encrypt data. If the proper environment is not loaded which will result in different PCR values, the TPM will be unable to decrypt the data.

7.6.5.1. Static Root of Trust for Measurement¶

Static Root of Trust for Measurement (SRTM) begins with measuring and verifying the integrity of the BIOS firmware. It then measures additional firmware modules, verifies their integrity, and adds each component’s measure to an SRTM value. The final value represents the expected state of boot path loads. SRTM stores results as one or more values stored in PCR storage. In SRTM, the CRTM resets PCRs 0 to 15 only at boot.

Using a Trusted Platform Module (TPM), as a hardware root of trust, measurements of platform components, such as firmware, bootloader, OS kernel, can be securely stored and verified. Cloud Infrastructure operators should ensure that the TPM support is enabled in the platform firmware, so that platform measurements are correctly recorded during boot time.

A simple process would work as follows;

The BIOS CRTM (Bios Boot Block) is executed by the CPU and used to measure the BIOS firmware.

The SHA1 hash of the result of the measurement is sent to the TPM.

The TPM stores this new result hash by extending the currently stored value.

The hash comparisons can validate settings as well as the integrity of the modules.

Cloud Infrastructure operators should ensure that OS kernel measurements can be recorded by using a TPM-aware bootloader (e.g. tboot, see https://sourceforge.net/projects/tboot/ or shim, see https://github.com/rhboot/shim), which can extend the root of trust up to the kernel level.

The validation of the platform measurements can be performed by TPM’s launch control policy (LCP) or through the remote attestation server.

7.6.5.2. Dynamic Root of Trust for Measurement¶

In Dynamic Root of Trust for Measurement (DRTM), the RTM for the running environment are stored in PCRs starting with PCR 17.

If a remote attestation server is used to monitor platform integrity, the operators should ensure that attestation is performed periodically or in a timely manner. Additionally, platform monitoring can be extended to monitor the integrity of the static file system at run-time by using a TPM aware kernel module, such as Linux IMA (Integrity Measurement Architecture), see https://sourceforge.net/p/linux-ima/wiki/Home, or by using the trust policies (see https://github.com/opencit/opencit/wiki/Open-CIT-3.2-Product-Guide) functionality of OpenCIT.

The static file system includes a set of important files and folders which do not change between reboots during the lifecycle of the platform. This allows the attestation server to detect any tampering with the static file system during the runtime of the platform.

7.6.6. Zero Trust Architecture¶

The sections “Remote Attestation/openCIT” and “Root of Trust for Measurements” provide methods to ensure the integrity of the infrastructure. The Zero Trust concept moves a step forward enabling to build secure by design cloud infrastructure, from hardware to applications. The adoption of Zero Trust principles mitigates the threats and attacks within an enterprise, a network or an infrastructure, ensuring a fine grained segmentation between each component of the system.

Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA), described in NIST SP 800-207 publication [25], assumes there is no implicit trust granted to assets or user accounts whatever their location or ownership. Zero trust approach focuses on protecting all types of resources: data, services, devices, infrastructure components, virtual and cloud components. Trust is never granted implicitly, and must be evaluated continuously.

ZTA principles applied to Cloud infrastructure components are the following:

Adopt least privilege configurations

Authentication and authorization required for each entity, service, or session

Fine grained segmentation

Separation of control plane and data plane

Secure internal and external communications

Monitor, test, and analyse security continuously

Zero Trust principles should also be applied to cloud-native applications. With the increasing use of these applications which are designed with microservices and deployed using containers as packaging and Kubernetes as an orchestrator, the security of east-west communications between components must be carefully addressed. The use of secured communication protocols brings a first level of security, but considering each component as non-trustworthy will minimize the risk for applications to be compromised. A good practice is to implement the proxy-based service mesh which will provide a framework to build a secured environment for microservices-based applications, offering services such as service discovery, authentication and authorisation policies enforcement, network resilience, and security monitoring capabilities. The two documents, NIST SP 800-204A(Building Secure Microservices-based Applications Using Service-Mesh Architecture) and NIST SP 800-204B(Attribute-based Access Control for Microservices-based Applications Using a Service Mesh), describe service mesh, and provide guidance for service mesh components deployment.

7.7. Software Supply Chain Security¶

Software supply chain attacks are increasing worldwide and can cause serious damages. Many enterprises and organisations are experiencing these threats. Aqua security’s experts estimated that software supply chain attacks have more than tripled in 2021. Reuters reported in August 2021 that the ransomware affecting Kaseya Virtual System Administration product caused downtime for over 1500 companies. In the case of the backdoor inserted in codecov software, hundreds of customers were affected. The Solarwinds attack detailed in Defending against SolarWinds attacks is another example of how software suppliers are targeted and, by rebound, their customers affected. Open-source code weaknesses can also be utilised by attackers, the Log4J vulnerability, impacting many applications, is a recent example in this field. When addressing cyber security, the vulnerabilities of software supply chain are often not taken into account. Some governments are already alerting and requesting actions to face these risks. The British government is hardening the law and standards of cyber security for the supply chain. The US government requested actions to enhance the software supply chain security. The security of the software supply chain is a challenge also pointed out by the European Network and Information Security Agency, ENISA, in the report NFV Security in 5G - Challenges and Best Practices.

7.7.1. Software security¶

Software supply chain security is crucial and is made complex by the greater attack surface provided by the many different supply chains in virtualised, containerised, and edge environments. All software components must be trusted, from commercial software, open-source code to proprietary software, as well as the integration of these components. The SAFECode white paper “Managing Security Risks Inherent in the Use of Third-party Components” provides a detailed risk management approach.

To secure software code, the following methods must be applied:

Use best practices coding such as design pattern recommended in the Twelve-Factor App or OWASP “Secure Coding Practices - Quick Reference Guide”

Do threat modelling, as described in the document “Tactical Threat Modeling” published by SAFECode

Use trusted, authenticated and identified software images that are provided by authenticated software distribution portals

Require suppliers to provide a Software Bill of Materials to identify all the components part of their product’s software releases with their dependencies, and eventually identify the open source modules

Test the software in a pre-production environment to validate integration

Detect vulnerabilities using security tools scanning and CVE (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) and apply remediation actions according to their severity rating

Report and remove vulnerabilities by upgrading components using authenticated software update distribution portals

Actively monitor the open source software repositories to determine if new versions have been released that address identified vulnerabilities discovered in the community

Secure the integration process by securing the software production pipeline

Adopt a DevSecOps approach and rely on testing automation throughout the software build, integration, delivery, deployment, and runtime operation to perform automatic security check, as described in section ”Infrastructure as a Code Security”

7.7.2. Open-Source Software Security¶

Open-source code is present in Cloud Infrastructure software from BIOS, host Operating System to virtualisation layer components, the most obvious being represented by Linux, KVM, QEMU, OpenStack, and Kubernetes. Workloads components can also be composed of open source code. The proportion of open-source code to an application source code can vary. It can be partial or total, visible or not. Open-source code can be upstream code coming directly from open-source public repositories or code within a commercial application or network function.

The strength of open-source code is the availability of code source developed by a community which maintains and improves it. Open-source code integration with application source code helps to develop and produce applications faster. But, in return, it can introduce security risks if a risk management DevSecOps approach is not implemented. The GSMA white paper “Open Networking & the Security of Open Source Software Deployment - Future Networks” alerts on these risks and addresses the challenges coming with open-source code usage. Amongst these risks for security, we can mention a poor code quality containing security flaws, an obsolete code with known vulnerabilities, and the lack of knowledge of open source communities’ branches activity. An active branch will come with bugs fixes, it will not be the case with an inactive branch. The GSMA white paper develops means to mitigate these security issues.

Poor code quality is a factor of risk. Open-source code advantage is its transparency, code can be inspected by tools with various capabilities such as open-source software discovery and static and dynamic code analysis.

Each actor in the whole chain of software production must use a dedicated internal isolated repository separated from the production environment to store vetted open-source content, which can include images, but also installer and utilities. These software packages must be signed and the signature verified prior to packages or images installation. Access to the repository must be granted by a dedicated authorization. The code must be inspected and vulnerabilities identified as described previously. After validating the software, it can be moved to the appropriate production repository.

7.7.3. Software Bill of Materials¶

In order to ensure software security, it is crucial to identify the software components and their origins. The Software Bill of Materials (SBOM), described by US NTIA (National Telecommunications and Information Administration), is an efficient and highly recommended tool to identify software components. The SBOM is an inventory of software components and the relationships between them. NTIA describes how to establish an SBOM and provides SBOM standard data formats. In case of vulnerability detected for a component, the SBOM inventory is an effective means to identify the impacted component and enable remediation.

A transparent software supply chain offers benefits for vulnerabilities remediation, but also for licensing management and it provides assurance of the source and integrity of components. To achieve and benefit from this transparency, a shared model must be supported by industry. This is the goal of the work performed by the US Department of Commerce and the National Telecommunications and Information administration (NTIA) and published, in July 2021, in the report “The Minimum Elements for a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM)” in July 2021. The document gives guidance and specifies the minimum elements for the SBOM, as a starting point.

A piece of software can be modelled as a hierarchical tree with components and subcomponents, each component should have its SBOM including, as a baseline, the information described in the following table.

Data Field |

Description |

|---|---|

Supplier Name |

The name of an entity that creates, defines, and identifies components. |

Component Name |

Designation assigned to a unit of software defined by the original supplier. |

Version of the Component |

Identifier used by the supplier to specify a change in software from a previously identified version. |

Other Unique Identifiers |

Other identifiers that are used to identify a component, or serve as a look-up key for relevant databases. |

Dependency Relationship |

Characterizing the relationship that an upstream component X is included in software Y. |

Author of SBOM Data |

The name of the entity that creates the SBOM data for this component. |

Timestamp |

Record of the date and time of the SBOM data assembly. |

Table 7-2: SBOM Data Fields components, source NTIA

Refer to the NTIA SBOM document for more details on each data field. Examples of commonly used identifiers are provided.

In order to use SBOMs efficiently and spread their adoption, information must be generated and shared in a standard format. This format must be machine-readable to allow automation. Proprietary formats should not be used. Multiple data formats exist covering baseline SBOM information. The three key formats, Software Package Data eXchange (SPDX), CycloneDX, and Software Identification Tags (SWID tags) are interoperable for the core data fields and use common data syntax representations.

SPDX is an open-source machine-readable format developed under the umbrella of the Linux Foundation. The SPDX specification 2.2 has been published as the standard ISO/IEC 5962:2021. It provides a language for communicating the data, licenses, copyrights, and security information associated with software components. With the SPDX specification 2.2, multiple file formats are available: YAML, JSON, RDF/XML, tag:value flat text, and xls spreadsheets.

CycloneDX was designed in 2017 for use with OWASP(Open Web Application Security Project) Dependency-Track tool, an open-source Component Analysis platform that identifies risk in the software supply chain. CycloneDX supports a wide range of software components, including: applications, containers, libraries, files, firmware, frameworks, Operating Systems. The CycloneDX project provides standards in XML, JSON, and Protocol Buffers, as well as a large collection of official and community supported tools that create or interoperate with the standard.

SWID Tags is an international XML-based standard used by commercial software publishers and has been published as the standard ISO/IEC 19770-2. The specification defines four types of SWID tags: primary, patch, corpus, and supplemental to describe a software component.

The SBOM should be integrated into the operations of the secure development life cycle, especially for vulnerabilities management. It should also evolve in time. When a software component is updated, a new SBOM must be created. The elements described in this section are part of an ongoing effort, improvements will be added in the future such as SBOM integrity and authenticity.

7.7.4. Vulnerability identification¶

Vulnerability management must be continuous: from development to runtime, not only on the development process, but during all the life of the application or workload or service. When a public vulnerability on a component is released, the update of the component must be triggered. When an SBOM recording the code composition is provided, the affected components will be easier to identify. It is essential to remediate the affected components as soon as possible, because the vulnerability can be exploited by attackers who can take the benefit of code weakness.

The CVE and the CVSS must be used to identify vulnerabilities and their severity rating. The CVE identifies, defines, and catalogues publicly disclosed cybersecurity vulnerabilities while the CVSS is an open framework to calculate the vulnerabilities’ severity score.

Various images scanning tools, including open-source tools like Clair or Trivy, are useful to audit images from security vulnerabilities. The results of vulnerabilities scan audit must be analysed carefully when it is applied to vendor offering packaged solutions; as patches are not detected by scanning tools, some components can be detected as obsolete.

7.8. Testing & certification¶

7.8.1. Testing demarcation points¶

It is not enough to just secure all potential points of entry and hope for the best, any Cloud Infrastructure architecture must be able to be tested and validated that it is in fact protected from attack as much as possible. The ability to test the infrastructure for vulnerabilities on a continuous basis is critical for maintaining the highest level of security possible. Testing needs to be done both from the inside and outside of the systems and networks. Below is a small sample of some of the testing methodologies and frameworks available.

OWASP testing guide

Penetration Testing Execution Standard, PTES

Technical Guide to Information Security Testing and Assessment, NIST 800-115

VULCAN, Vulnerability Assessment Framework for Cloud Computing, IEEE 2013

Penetration Testing Framework, VulnerabilityAssessment.co.uk

Information Systems Security Assessment Framework (ISSAF)

Open Source Security Testing Methodology Manual (OSSTMM)

FedRAMP Penetration Test Guidance (US Only)

CREST Penetration Testing Guide

Insuring that the security standards and best practices are incorporated into the Cloud Infrastructure and architectures must be a shared responsibility, among the Telecommunications operators interested in building and maintaining the infrastructures in support of their services, the application vendors developing the network services that will be consumed by the operators, and the Cloud Infrastructure vendors creating the infrastructures for their Telecommunications customers. All of the parties need to incorporate security and testing components, and maintain operational processes and procedures to address any security threats or incidents in an appropriate manner. Each of the stakeholders need to contribute their part to create effective security for the Cloud Infrastructure.

7.8.2. Certification requirements¶

Security certification should encompass the following elements:

Security test cases executed and test case results.

Industry standard compliance achieved (NIST, ISO, PCI, FedRAMP Moderate etc.).

Output and analysis from automated static code review, dynamic tests, and penetration tests with remediation of Medium/High/Critical security issues. Tools used for security testing of software being released must be shared.

Details on un-remediated low severity security issues must be shared.

Threat models performed during design phase. Including remediation summary to mitigate threats identified.

Details on un-remediated low severity security issues.

Any additional Security and Privacy requirements implemented in the software deliverable beyond the default rules used security analysis tools.

Resiliency tests run (such as hardware failures or power failure tests)

7.9. Cloud Infrastructure Regulatory Compliance¶

Evolving cloud adoption in the telecom industry, now encroaching on its inner sanctum of network services, undoubtedly brings many benefits for the network operators and their partners, and ultimately to the end consumers of the telecommunication services. However, it also brings compliance challenges that can seem overwhelming. The telecommunication industry players can reduce this overwhelm by arming themselves with information about which laws they need to comply with, why, and how.

The costs of non-compliance can be very serious. Organisations may not only have to contend with hefty fines and possible lawsuits, but they may also even end up losing their reputation and eventually losing customers, with an obvious adverse impact on revenues and profitability.

Compliance means that an operator’s systems, processes, and workflows align with the requirements mandated by the regulatory regimes imposed by the relevant governmental and industry regulatory bodies. The need for compliance extends to the cloud, so operators must ensure that any data transferred to and out, and stored in their cloud infrastructure complies with all relevant data protection, including data residency, and privacy laws.

To comply with the laws that apply to an operator’s business, the proper security controls need to be applied. The applicable laws have very specific rules and constraints about how companies can collect, store and process data in the cloud. To satisfy these constraints and ensure compliance, the telecom operators should work with their cloud providers and other partners to implement strong controls. To speed up this process, the operators may start from augmenting their existing cybersecurity/information security frameworks to guide their security programs to implement controls to secure their cloud infrastructure and to achieve regulatory compliance. This process can also be assisted by support from the cloud providers and third parties, who can offer their well-proven compliance offerings, resources, audit reports, dashboards, and even some security controls as a service.

After implementing these controls, companies need to train their employees and partners to use the controls properly to protect data and maintain the required compliance posture. This is a critical requirement to maintain compliance via enforcing relevant security guiderails in all aspects of every-day operations, as well as for ensuring a process of regular assessment of the compliance posture.

Because of the localised nature of the regulatory regimes, this document may not provide any specific compliance requirements. However, some examples provided below, can be of assistance for an operator’ compliance considerations.

Commonly used (in many jurisdictions) compliance audit reports are based on SOC 2 report from the SOC (System and Organization Controls) suite of services, standardised by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) and meant for service organizations like cloud providers; see AICPA SOC. A SOC 2 report shows whether the cloud provider has implemented the security controls required to comply with the AICPA’s five “trust services criteria”: security, availability, confidentiality, processing integrity, and privacy. Operators should request SOC 2 report from their cloud providers (public or internal to their organisations). There are two flavours of SOC 2: type 1 report shows the status and suitability of the provider’s controls at a particular moment, while type 2 report shows the operational effectiveness of these controls over a certain period. In cases when a cloud provider is not willing to share SOC 2 report because it may contain sensitive information, operators can ask for the SOC 3 report which is intended as a general-use report but can still help assess the provider’s compliance posture.

Some cloud providers also provide attestations (or in case of private cloud, telecoms should seek such attestation) to show which of their cloud services have achieved compliance with different frameworks such as mentioned above SOC, but also commonly used frameworks like OWASP, ISAE, NIST, ETSI and ISO 27000 series, and more geographically localised standard frameworks like NIST (as used in the U.S.A.), ENISA, GDPR, ISM.

The use of the ISO 2700s, OWASP, ISAE, NIST and ETSI security frameworks for cloud infrastructure is referenced in “Common Security Standards” and “Compliance with Standards” sections.

Examples of regulatory frameworks are briefly presented below. It is intended to expand this list of examples in the future releases to cover more jurisdictions and to accommodate changes in the rapidly evolving security and regulatory landscape.

7.9.1. U.S.A.¶

In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulates interstate and international communications by radio, television, wire, satellite and cable in all 50 states, the District of Columbia and U.S. territories. The FCC is an independent U.S. government agency overseen by Congress. The Commission is the federal agency responsible for implementing and enforcing America’s communications laws and regulations.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework, compliance is mandatory for the supply chain for all U.S.A. federal government agencies. Because this framework references globally accepted standards, guidelines and practice, telecom organisations in the U.S.A. and worldwide can use it to efficiently operate in a global environment and manage new and evolving cybersecurity risks in the cloud adoption area.

7.9.2. European Union (EU)¶

The overall telecommunications regulatory framework in the European Union (EU) is provided in The European Electronic Communications Code.

The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) contributes to EU cyber policy, enhances the trustworthiness of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) products, services and processes with cybersecurity certification schemes, cooperates with Member States and EU bodies, and helps Europe prepare for the cyber challenges of tomorrow. In particular, ENISA is carrying out a risk assessment of cloud computing and works on the European Cybersecurity Certification Scheme (EUCS) for Cloud Services scheme, which looks into the certification of the cybersecurity of cloud services,

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a set of EU regulations that governs how data should be protected for EU citizens. It affects organisations that have EU-based customers, even if they are not based in the EU themselves.

7.9.3. UK¶

Office of Communications (Ofcom) is the regulator and competition authority for the UK communications industries. It regulates the TV and radio sectors, fixed line telecoms, mobiles, postal services, plus the airwaves over which wireless devices operate.

Security of Networks & Information Systems NIS Regulations in UK, provide legal measures to boost the level of security (both cyber & physical resilience) of network and information systems for the provision of essential services and digital services.

The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) acts as a bridge between industry and government, providing a unified source of advice, guidance and support on cyber security, including the management of cyber security incidents. From this perspective it is critical for the cloud related security in the UK telecommunications industry. The NCSC is not a regulator. Within the general UK cyber security regulatory environment, including both NIS and GDPR, the NCSC’s aim is to operate as a trusted, expert and impartial advisor to all interested parties. The NCSC supports Security of Networks & Information Systems (NIS) Regulations.

The data protection in UK is controlled by Data Protection Act 2018, which is UK’s implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

7.9.4. Australia¶

In Australia, the telecommunication sector is regulated by the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC). The ACCC is responsible for the economic regulation of the communications sector, including telecommunications and the National Broadband Network (NBN), broadcasting and content sectors.

From the cloud services security perspective, the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) produced Information Security Manual (ISM), is of particular importance. The purpose of the ISM is to outline a cyber security framework that organisations can apply, using their risk management framework, to protect their information and systems from cyber threats. The ISM is intended for Chief Information Security Officers, Chief Information Officers, cyber security professionals and information technology managers. While in general ISM provides guidelines rather than mandates, several security controls are by law mandatory for cloud-based services used by the Australian telecommunication operators, in situation involving strategically important data and/or services.

Australia regulates data privacy and protection through a mix of federal, state and territory laws. The federal Privacy Act 1988 (currently under review by The Australian Government) and the Australian Privacy Principles (APP) contained in the Privacy Act regulate the handling of personal information by relevant entities and under the Privacy Act. The Privacy Commissioner has authority to conduct investigations, including own motion investigations, to enforce the Privacy Act and seek civil penalties for serious and egregious breaches or for repeated breaches of the APPs where an entity has failed to implement remedial efforts.

7.10. Consolidated Security Requirements¶

7.10.1. System Hardening¶

Ref |

Requirement |

Definition/Note |

|---|---|---|

req.sec.gen.001 |

The Platform must maintain the specified configuration. |

|

req.sec.gen.002 |

All systems part of Cloud Infrastructure must support password hardening as defined in CIS Password Policy Guide https://www.cisecu rity.org/white-papers/cis-password-policy-guide. |

Hardening: CIS Password Policy Guide |

req.sec.gen.003 |

All servers part of Cloud Infrastructure must support a root of trust and secure boot. |

|

req.sec.gen.004 |

The Operating Systems of all the servers part of Cloud Infrastructure must be hardened by removing or disabling unnecessary services, applications and network protocols, configuring operating system user authentication, configuring resource controls, installing and configuring additional security controls where needed, and testing the security of the Operating System. |

NIST SP 800-123 |

req.sec.gen.005 |

The Platform must support Operating System level access control. |

|

req.sec.gen.006 |

The Platform must support Secure logging. Logging with root account must be prohibited when root privileges are not required. |

|

req.sec.gen.007 |

All servers part of Cloud Infrastructure must be Time synchronized with authenticated Time service. |

|

req.sec.gen.008 |

All servers part of Cloud Infrastructure must be regularly updated to address security vulnerabilities. |

|

req.sec.gen.009 |

The Platform must support Software integrity protection and verification and must scan source code and manifests. |

|

req.sec.gen.010 |

The Cloud Infrastructure must support encrypted storage, for example, block, object and file storage, with access to encryption keys restricted based on a need to know. Controlled Access Based on the Need to Know https://www.ci security.org/controls/controlled-access-based-on -the-need-to-know. |

|

req.sec.gen.011 |

The Cloud Infrastructure should support Read and Write only storage partitions (write only permission to one or more authorized actors). |

|

req.sec.gen.012 |

The Operator must ensure that only authorized actors have physical access to the underlying infrastructure. |

|

req.sec.gen.013 |

The Platform must ensure that only authorized actors have logical access to the underlying infrastructure. |

|

req.sec.gen.014 |

All servers part of Cloud Infrastructure should support measured boot and an attestation server that monitors the measurements of the servers. |

|

req.sec.gen.015 |

Any change to the Platform must be logged as a security event, and the logged event must include the identity of the entity making the change, the change, the date and the time of the change. |

Table 7-3: System hardening requirements

7.10.2. Platform and Access¶

Ref |

Requirement |

Definition/Note |

|---|---|---|

req.sec.sys.001 |

The Platform must support authenticated and secure access to API, GUI and command line interfaces. |

|

req.sec.sys.002 |

The Platform must support Traffic Filtering for workloads (for example, Fire Wall). |

|

req.sec.sys.003 |

The Platform must support Secure and encrypted communications, and confidentiality and integrity of network traffic. |

|

req.sec.sys.004 |

The Cloud Infrastructure must support authentication, integrity and confidentiality on all network channels. |

A secure channel enables transferring of data that is resistant to overhearing and tampering. |

req.sec.sys.005 |

The Cloud Infrastructure must segregate the underlay and overlay networks. |

|

req.sec.sys.006 |

The Cloud Infrastructure must be able to utilize the Cloud Infrastructure Manager identity lifecycle management capabilities. |

|

req.sec.sys.007 |

The Platform must implement controls enforcing separation of duties and privileges, least privilege use and least common mechanism (Role-Based Access Control). |

|

req.sec.sys.008 |

The Platform must be able to assign the Entities that comprise the tenant networks to different trust domains. |

Communication between different trust domains is not allowed, by default. |

req.sec.sys.009 |

The Platform must support creation of Trust Relationships between trust domains. |

These maybe uni-directional relationships where the trusting domain trusts anther domain (the “trusted domain”) to authenticate users for them or to allow access to its resources from the trusted domain. In a bidirectional relationship both domain are “trusting” and “trusted”. |

req.sec.sys.010 |

For two or more domains without existing trust relationships, the Platform must not allow the effect of an attack on one domain to impact the other domains either directly or indirectly. |

|

req.sec.sys.011 |

The Platform must not reuse the same authentication credential (e.g., key-pair) on different Platform components (e.g., on different hosts, or different services). |

|

req.sec.sys.012 |

The Platform must protect all secrets by using strong encryption techniques, and storing the protected secrets externally from the component. |

E.g., in OpenStack Barbican. |

req.sec.sys.013 |

The Platform must provide secrets dynamically as and when needed. |

|

req.sec.sys.014 |

The Platform should use Linux Security Modules such as SELinux to control access to resources. |

|

req.sec.sys.015 |

The Platform must not contain back door entries (unpublished access points, APIs, etc.). |

|

req.sec.sys.016 |

Login access to the platform’s components must be through encrypted protocols such as SSH v2 or TLS v1.2 or higher. |

Hardened jump servers isolated from external networks are recommended |

req.sec.sys.017 |

The Platform must provide the capability of using digital certificates that comply with X.509 standards issued by a trusted Certification Authority. |

|

req.sec.sys.018 |

The Platform must provide the capability of allowing certificate renewal and revocation. |

|

req.sec.sys.019 |

The Platform must provide the capability of testing the validity of a digital certificate (CA signature, validity period, non-revocation, identity). |

|

req.sec.sys.020 |

The Cloud Infrastructure architecture should rely on Zero Trust principles to build a secure by design environment. |

Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) described in NIST SP 800-207 |

Table 7-4: Platform and access requirements

7.10.3. Confidentiality and Integrity¶

Ref |

Requirement |

Definition/Note |

|---|---|---|

req.sec.ci.001 |

The Platform must support Confidentiality and Integrity of data at rest and in transit. |

|

req.sec.ci.002 |

The Platform should support self-encrypting storage devices. |

|

req.sec.ci.003 |

The Platform must support Confidentiality and Integrity of data related metadata. |

|

req.sec.ci.004 |

The Platform must support Confidentiality of processes and restrict information sharing with only the process owner (e.g., tenant). |

|

req.sec.ci.005 |

The Platform must support Confidentiality and Integrity of process-related metadata and restrict information sharing with only the process owner (e.g., tenant). |

|

req.sec.ci.006 |

The Platform must support Confidentiality and Integrity of workload resource utilization (RAM, CPU, Storage, Network I/O, cache, hardware offload) and restrict information sharing with only the workload owner (e.g., tenant). |

|

req.sec.ci.007 |

The Platform must not allow Memory Inspection by any actor other than the authorized actors for the Entity to which Memory is assigned (e.g., tenants owning the workload), for Lawful Inspection, and by secure monitoring services. |

Admin access must be carefully regulated. |

req.sec.ci.008 |

The Cloud Infrastructure must support tenant networks segregation. |

|

req.sec.ci.009 |

For sensitive data encryption, the key management service should leverage a Hardware Security Module to manage and protect cryptographic keys. |

Table 7-5: Confidentiality and integrity requirements

7.10.4. Workload Security¶

Ref |

Requirement |

Definition/Note |

|---|---|---|

req.sec.wl.001 |

The Platform must support Workload placement policy. |

|

req.sec.wl.002 |

The Cloud Infrastructure must provide methods to ensure the platform’s trust status and integrity (e.g. remote attestation, Trusted Platform Module). |

|

req.sec.wl.003 |

The Platform must support secure provisioning of workloads. |

|

req.sec.wl.004 |

The Platform must support Location assertion (for mandated in-country or location requirements). |

|

req.sec.wl.005 |

The Platform must support the separation of production and non-production Workloads. |

|

req.sec.wl.006 |

The Platform must support the separation of Workloads based on their categorisation (for example, payment card information, healthcare, etc.). |

|

req.sec.wl.007 |

The Operator should implement processes and tools to verify NF authenticity and integrity. |

Table 7-6: Workload security requirements

7.10.5. Image Security¶

Ref |

Requirement |

Definition/Note |

|---|---|---|

req.sec.img.001 |

Images from untrusted sources must not be used. |

|

req.sec.img.002 |

Images must be scanned to be maintained free from known vulnerabilities. |

|

req.sec.img.003 |

Images must not be configured to run with privileges higher than the privileges of the actor authorized to run them. |

|

req.sec.img.004 |

Images must only be accessible to authorized actors. |

|

req.sec.img.005 |

Image Registries must only be accessible to authorized actors. |

|

req.sec.img.006 |

Image Registries must only be accessible over secure networks that enforce authentication, integrity and confidentiality. |

|

req.sec.img.007 |

Image registries must be clear of vulnerable and out of date versions. |

|

req.sec.img.008 |

Images must not include any secrets. Secrets include passwords, cloud provider credentials, SSH keys, TLS certificate keys, etc. |

|

req.sec.img.009 |

CIS Hardened Images should be used whenever possible. |

|

req.sec.img.010 |

Minimalist base images should be used whenever possible. |

Table 7-7: Image security requirements

7.10.6. Security LCM¶

Ref |

Requirement |

Definition/Note |

|---|---|---|

req.sec.lcm.001 |

The Platform must support Secure Provisioning, Availability, and Deprovisioning (Secure Clean-Up) of workload resources where Secure Clean-Up includes tear-down, defence against virus or other attacks. |

Secure clean-up: tear-down, defending against virus or other attacks, or observing of cryptographic or user service data. |

req.sec.lcm.002 |

Cloud operations staff and systems must use management protocols limiting security risk such as SNMPv3, SSH v2, ICMP, NTP, syslog and TLS v1.2 or higher. |

|

req.sec.lcm.003 |

The Cloud Operator must implement and strictly follow change management processes for Cloud Infrastructure, Cloud Infrastructure Manager and other components of the cloud, and Platform change control on hardware. |

|

req.sec.lcm.004 |

The Cloud Operator should support automated templated approved changes. |

Templated approved changes for automation where available. |

req.sec.lcm.005 |

Platform must provide logs and these logs must be regularly monitored for anomalous behaviour. |

|

req.sec.lcm.006 |

The Platform must verify the integrity of all Resource management requests. |

|

req.sec.lcm.007 |

The Platform must be able to update newly instantiated, suspended, hibernated, migrated and restarted images with current time information. |

|

req.sec.lcm.008 |

The Platform must be able to update newly instantiated, suspended, hibernated, migrated and restarted images with relevant DNS information. |

|

req.sec.lcm.009 |

The Platform must be able to update the tag of newly instantiated, suspended, hibernated, migrated and restarted images with relevant geolocation (geographical) information. |

|

req.sec.lcm.010 |

The Platform must log all changes to geolocation along with the mechanisms and sources of location information (i.e. GPS, IP block, and timing). |

|

req.sec.lcm.011 |

The Platform must implement Security life cycle management processes including the proactive update and patching of all deployed Cloud Infrastructure software. |

|

req.sec.lcm.012 |

The Platform must log any access privilege escalation. |

Table 7-8: Security LCM requirements

7.10.7. Monitoring and Security Audit¶

The Platform is assumed to provide configurable alerting and notification capability and the operator is assumed to have systems, policies and procedures to act on alerts and notifications in a timely fashion. In the following the monitoring and logging capabilities can trigger alerts and notifications for appropriate action. In general, it is a good practice to have the same security monitoring and auditing capabilities in both production and non-production environments. However, we distinguish between requirements for Production Platform (Prod-Platform) and Non-production Platform (NonProd-Platform) as some of the requirements may in practice need to differ, see section Security of Production and Non-production Environments for the general discussion of this topic. In the table below, when a requirement mentions only Prod-Platform, it is assumed that this requirement is optional for NonProd-Platform. If a requirement does not mention any environment, it is assumed that it is valid for both Prod-Platform and NonProd-Platform.

Ref |

Requirement |

Definition/Note |

|---|---|---|

req.sec.mon.001 |

The Prod-Platform and NonProd-Platform must provide logs. The logs must contain the following fields: event type, date/time, protocol, service or program used for access, success/failure, login ID or process ID, IP address, and ports (source and destination) involved. |

|

req.sec.mon.002 |

The logs must be regularly monitored for events of interest. |

|

req.sec.mon.003 |

Logs must be time synchronised for the Prod-Platform as well as for the NonProd-Platform. |

|

req.sec.mon.004 |

The Prod-Platform and NonProd-Platform must log all changes to time server source, time, date and time zones. |

|

req.sec.mon.005 |

The Prod-Platform and NonProd-Platform must secure and protect all logs (containing sensitive information) both in-transit and at rest. |

|

req.sec.mon.006 |

The Prod-Platform and NonProd-Platform must Monitor and Audit various behaviours of connection and login attempts to detect access attacks and potential access attempts and take corrective actions accordingly. |

|

req.sec.mon.007 |

The Prod-Platform and NonProd-Platform must Monitor and Audit operations by authorized account access after login to detect malicious operational activity and take corrective actions. |

|